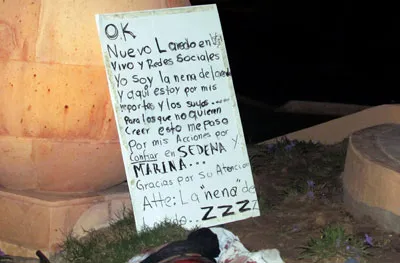

María Elizabeth Macías Castro’s killers made sure their actions were understood. In a macabre, carefully orchestrated mise-en-scene, they placed her body in front of a poster with the ominous note. Nearby they left a computer keyboard, with a pair of headphones on her decapitated head.

The murder of the Mexican journalist in the city of Nuevo Laredo on Saturday marks a potential watershed: It is the first case CPJ has documented in which someone was murdered in direct retaliation for journalism posted on social media. If the ghoulish crime scene and props weren’t illustrative enough, the note left by the murderers left no doubt. “Ok. Nuevo Laredo Live and social media, I am the Girl from Laredo and I am here because of my reports and yours… ZZZZ.” The “ZZZZ” signature suggests a link to the vicious Zetas drug cartel.

More on this issue

• When a bug fix can

save a journalist’s life

Local journalists told CPJ that the note referred to Macías Castro’s online pseudonym “La NenaDLaredo” (The girl from Laredo), under which she posted information about crime on Twitter and on the website Nuevo Laredo en vivo (Nuevo Laredo Live). The Mexican website Animal Político reported that Macías moderated the chat forum of Nuevo Laredo en vivo, where users often denounced organized crime and the authorities, and that her last posted comment before her death was “Hunting rats, if you see where they run, denounce them.” Another message from Nuevo Laredo en vivo‘s Twitter account read, “Raid by federal police on false document makers on bridge II, it was time.” It is not known how Macías’ killers discovered her identity.

Macías, 39, had reporting and administrative responsibilities for the local daily Primera Hora, local journalists told CPJ, although the newspaper would not confirm her employee status. It is no surprise that Macías would choose to publish her criticisms anonymously online, rather than in the pages of a newspaper. Throughout Mexico, but especially in the north, unrelenting violence by criminal groups has terrorized the local press into silence. Primera Hora, a local journalist told CPJ, has not reported on crime in years, illustrating the rule and not the exception. In the face of this rampant censorship and a near-complete void of information, Mexican citizens, and many journalists, are turning to social media and online forums to share news and inform each other.

So it should be no shock that drug cartels are turning their attention to the Internet. On September 13, the bodies of two young people, who were not identified, were hung from a pedestrian overpass in Nuevo Laredo. Press accounts said notes left with the bodies warned against writing on websites.

In this landscape, where impunity for crimes against journalists usually reigns, a local editor told CPJ that journalists are trying to devise measures to protect themselves. The editor’s newspaper has guidelines for Internet use, which include sensible rules such as putting social media posts under the generic username of the newspaper, and forbidding journalists from posting anything related to crime under their personal accounts.

Tragically, however, Macías’ murder shows that in the face of seemingly all-knowing, all-powerful organized crime groups, the Internet’s veil of anonymity may no longer offer protection.