This month, the prosecutor-general of Kyrgyzstan, Aida Salyanova, told the Committee to Protect Journalists that her office is working hard to fight corruption and ensure transparency in government activities.

We are not convinced.

CPJ has long called on Kyrgyz authorities to reopen the case of journalist and human rights defender Azimjon Askarov, who is serving life in prison for the murder of a policeman–a trumped-up charge that CPJ and other human rights groups have determined is in retaliation for Askarov’s exposure of wrongdoing by police and prosecutors.

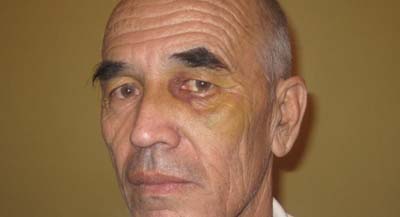

Askarov, a recipient of CPJ’s 2012 International Press Freedom Awards, is known for his investigations into government corruption and human rights abuses by law enforcement. He regularly documented abuses and pressed for justice for victims. Four years ago, amid violence between ethnic Kyrgyz and Uzbeks in the southern part of the country, he was working when he was arrested, beaten, prosecuted in a deeply flawed trial, and imprisoned by the very the same authorities he had criticized in his reporting, according to CPJ research.

Salyanova met with CPJ and other rights groups on July 2 in Washington, D.C., during an exchange visit with the U.S. Department of Justice. At the meeting, where she spoke through an interpreter, she said she has opened more than 20 cases against judges, prosecutors, and other law enforcement officers to investigate allegations of abuse of office. Yet there are no reports that any of the officials responsible for locking up Askarov have been investigated, despite allegations that he was tortured in custody, his defense lawyer and witnesses were harassed and intimidated, and his trial included a number of procedural violations. When Askarov’s case was briefly reopened recently, following an appeal by the journalist’s defense, the same prosecutors who had been targets of Askarov’s journalistic investigations were again given charge of the case. Unsurprisingly, they found no evidence of procedural violations or other wrongdoing.

Salyanova acknowledged calls to have the case reopened, but said the testimony backing Askarov’s version of events came from his relatives and is therefore invalid. This directly contradicts CPJ’s letter to the prosecutor-general, in February 2013, in which we reminded her that Askarov’s defense team began gathering evidence from witnesses immediately after the journalist was convicted in 2010. The witnesses were not given the opportunity to step forward during the proceedings–they were either ignored by the court or intimidated into silence. This substantially limited Askarov’s defense and violated his right to a fair trial. A number of the witnesses’ statements to the defense corroborated Askarov’s own statements that he was not present at the scene of the crime for which he was convicted.

Askarov’s lawyers told CPJ that they submitted their witness statements to Salyanova’s office as early as May 2012. But it is a stretch to expect that the same prosecutors whose abuses Askarov exposed in his stories; who fabricated evidence against him; and who sought his life imprisonment would declare their own case against Askarov invalid. This case needs to be examined by an independent team and in a transparent manner.

Salyanova told CPJ that Askarov was asked whether he felt that the Kyrgyz security agencies were biased against him, and that he had replied “no.” What prisoner who had been beaten in custody would give a different answer? (Salyanova also said her office was clamping down on torture, but allegations of Askarov’s torture have yet to be addressed).

The State Department and the Helsinki Committee of the U.S. Congress also raised concerns about Askarov’s case and the broader reforms needed in Kyrgyzstan’s judicial system, particularly for those convicted in relation to the June 2010 violence. Laura Carey, Deputy Director for the Office of South and Central Asia at the State Department’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, called on Salyanova to release Askarov on humanitarian grounds because of his deteriorating health. We at CPJ call on the prosecutor-general to order a thorough, independent, and transparent investigation of the circumstances surrounding Askarov’s detention, prosecution, and imprisonment–and to release him in the meantime.

Until then, Salyanova’s assertion that Kyrgyzstan is undergoing genuine judicial reform remains only an assertion.