For 23 years Godfrey Mwampembwa has been a prominent and quick-witted observer of the political scene in East Africa. But all that changed last month when the cartoonist, known as Gado, was told his contract at Kenya’s biggest newspapers, the Nation, would not be renewed.

Gado, who is one of Africa’s most celebrated cartoonists, said no reason was given for the termination of his contract–the Nation management said in an interview with Africa Uncensored it was a normal contractual parting of ways–but the cartoonist told CPJ he firmly suspects the paper was under pressure from government officials.

He told CPJ he has been under considerable pressure for months from representatives of Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta and Deputy President William Ruto, including legal action over his cartoons and repeated phone calls to the paper’s management and himself.

“It is no secret that there were many in government who didn’t like my cartoons over the years. But we had grown used to that and the Nation thankfully consistently pushed back. Things changed in 2013 after a new government came into place and the pressure became far more intense. I have no doubt that the Nation crumbled, which is quite sad and should be seen in the broader context of efforts by those in government to control the press,” he said.

Tom Mshindi, editor-in-chief of the Nation Media Group, denied that pressure from the government led to Gado’s contract being ended. “Gado has been drawing critical and satirical cartoons for many years and Nation has continued to have him,” he told CPJ by email.

Dennis Itumbi, a spokesman for Kenyatta, denied that the Kenyan authorities leaned on newspapers to influence coverage or weed out critics. He told CPJ: “The president and deputy president believe in a free press. They have a whole manifesto to deliver on which includes safeguarding freedom of the press. We want business to thrive not die.”

Itumbi would not discuss specific claims about efforts to pressure editors and newspaper proprietors, telling CPJ those issues should be aired in court when “aggrieved journalists sue their employers.”

A July 2015 CPJ special report on conditions for the press since Kenyatta took power found that journalists in the country “are vulnerable to legal harassment, threats, or attack, while news outlets are manipulated by advertisers or politician-owners.”

The government has championed several pieces of legislation that would sharply limit the ability of journalists to report freely. CPJ documented how Parliament passed a law in October which would have imposed a fine of up to USD$5,000 or two years in jail, or both, on any journalist found guilty of defaming the Kenyan parliament or its members; and how Parliament endorsed an amendment to security laws in December 2014 that would have allowed Kenyan security forces to intercept communications and imprison journalists for covering anti-terrorism investigations and operations.

The anti-terror law was successfully challenged in the courts and parliament retreated on the defamation law in the face of a public outcry, but that has not stopped authorities from taking action. Recent examples include the arrest of parliamentary editor John Ngirachu in November last year. He was detained and questioned after declining to reveal the source of a story about corruption, according to reports; the detention and questioning of several bloggers, almost all of them critics of the government who, according to reports, were detained over their social media posts; and the firing of Denis Galava, a managing editor at the Nation, who was sacked over a New Year’s editorial critical of the Kenyatta administration, reports said. The Nation issued a statement saying he had not followed the correct procedure in writing the editorial.

Slideshow: Gado’s work

« Previous Image | Next Image »

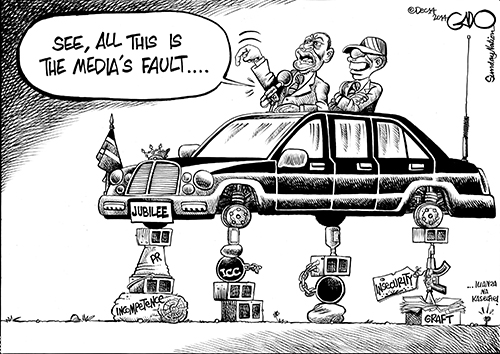

This December 2014 cartoon shows the president, in a car propped up on blocks reading “ICC” and “graft,” blaming the media for Kenya’s problems. Since Kenyatta came to power, the country’s critical press has come under increasing pressure. (Gado)

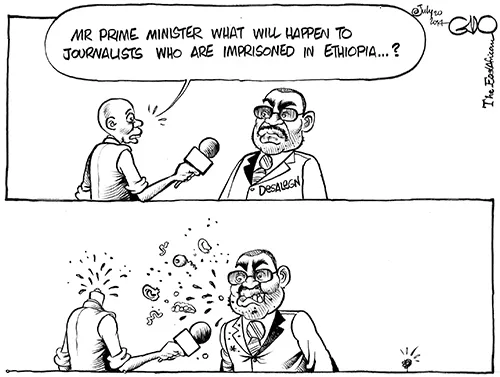

Gado is also critical of Ethiopia’s leadership, with this 2014 cartoon showing the prime minister reacting to a question on the number of journalists jailed in Ethiopia. (Gado)

Kenya’s president and deputy president are depicted giving each other a high-five while riding skateboards. Gado says he was asked to stop drawing them in shackles. (Gado)

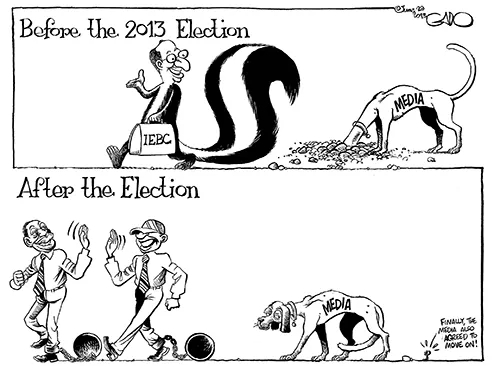

This 2013 cartoon gives Gado’s views on how the media covered Kenya’s elections. A 2015 CPJ report found the press freedom climate has becoming increasingly restrictive. (Gado)

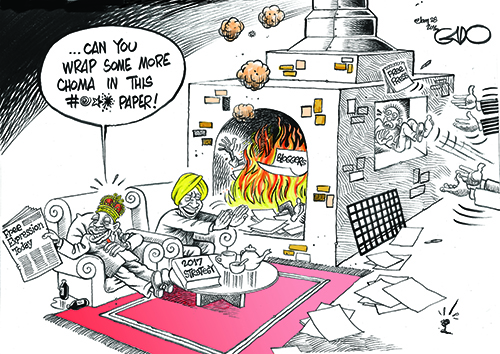

Gado depicts journalists and bloggers being thrown on a fire in this January 2016 cartoon. He told CPJ he has come under pressure over his critical drawings. (Gado)

Gado–described by the prominent South African cartoonist Jonathan Shapiro as “the most important cartoonist in Africa“–had commented on the shrinking space for press freedom in Kenya in a July 2015 Financial Times interview. The cartoonist said: “I think that freedom of expression of the media in Kenya has been on the right track until recently. We’ve seen fight back from this administration. They’ve complained bitterly about lots of thing about me–I’ve no problem about that–but what we have seen with the current administration is that they have been trying to roll back the gains that had been achieved in the past.”

Gado says he was summoned to the office of the Nation Media Group’s then chief executive Linus Gitahii n March 2015. He told CPJ that Gitahi persuaded him to take a sabbatical, telling the cartoonist Tanzania’s then-president Jakaya Kikwete objected to a cartoon published in January 2015 in the regional weekly The East African, which is part of the Nation Media Group.

The Kikwete administration had banned distribution of The East African in Tanzania for operating without a license and Gitahi told Gado that he needed to explain to Tanzanian authorities that some action had been taken against the cartoonist, Gado said. (The ban on The East African was lifted in January.)

In an interview last week with Kenyan online outlet Africa Uncensored, Gitahi denied there was any pressure over the cartoon and said he and Gado had mutually agreed on the cartoonist taking a sabbatical.

Mshindi gave a similar account to CPJ, saying that Gitahi allowed Gado to take a sabbatical that the cartoonist had requested. “It was a mutually agreed decision and had nothing to do with the cartoon although it did offend Tanzania’s authorities,” he said.

Gado told CPJ that toward the end of the year-long sabbatical the Nation informed him that his contract would not be renewed. Many Kenyans criticized the move on social media as yet another example of attempts to muzzle the press.

In an interview with the online publication Africa Uncensored, the Nation‘s editor-in-chief Mshindi said there was nothing unusual about the decision to end his contract. “The only thing that I want to say is that a contractual relationship between an employer and an employee is very clear and any one person can end that relationship if they feel that there is sufficient reason for that to happen.” Mshindi said.

In a statement to his lawyers Gado, who is contesting his dismissal, alleged that he and the management of the Nation had come under severe pressure to tone down caricatures which lampooned the authorities.

According to the statement, viewed by CPJ, in 2009 Kenyatta, the then Kenyan finance minister, sued Gado after he drew a series of caricatures about a political storm which broke after the minister said “a typing error”may have been to blame for an extra $120 million added to the Supplementary Budget. The case has not yet been resolved.

The statement says Gado was called in by the editors in 2014 and told that the board was under pressure from state authorities to get him to stop depicting the president and deputy president in shackles, after they were indicted by the International Criminal Court.

On another occasion, after he caricatured the deputy president in relation to the allegedly illegal appropriation of a school playing field, Gado described receiving a call from the deputy president’s office complaining that the cartoon was unfair. Early in February 2015, Mshindi called Gado in for a meeting about the depiction of the deputy president and asked him not to persist with the drawings, according to Gado’s statement.

Mshindi told CPJ that neither claim was true. “The board does not get involved in the minutiae of what goes on in the newsrooms. We have a clear policy on this,” he said in an email. “As editor in chief, I discuss all content direction with my editors and key contributors. I did not instruct Gado to end his depictions of the deputy president and any cursory review if the papers will confirm this.”

In his legal statement, Gado said, “I was astounded by his assertion because I was being given boundaries to operate within. I protested to him that while the paper had the right not to publish what I draw, I would not agree to politicians dictating what I should draw or what I should not. I made it clear to him that I did not share his views. We left the matter at that. As an editorial cartoonist, I felt less protected and more vulnerable.”

Gado told CPJ, “For a long time, many countries in Africa looked up to Kenya as an example when it came to the field of press freedom. We are seeing a clear and systematic effort by the state to roll back those gains which is very worrying.” Gado added, “The media is not perfect. But it serves as an important check on executive excesses and therefore makes an important contribution to the health of any society. The state should not seek to monopolize the information the public has access to.”

–Reporting by Kerry Paterson, CPJ’s Africa research associate, and Murithi Mutiga, CPJ’s East Africa correspondent. Mutiga is a columnist and consulting editor for the Sunday Nation, which is part of the Nation Media Group.