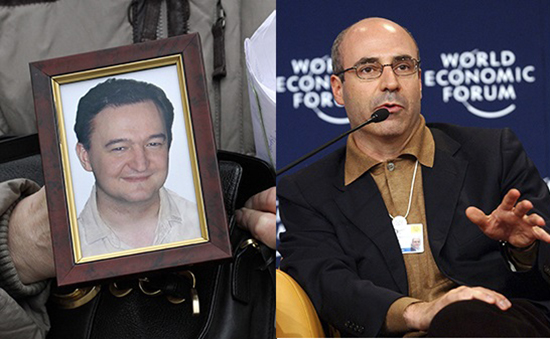

Sidebar: Raising the Cost of Impunity, in the Name of Magnitsky

Sergei Magnitsky, 37, a Russian lawyer and tax adviser, died in November 2009 after spending several months in Moscow’s Butyrka prison, which is known for its harsh conditions. An independent report by the Moscow Public Oversight Commission, a Russian NGO that monitors human rights in detention facilities, concluded that Magnitsky had been kept in torturous conditions and denied treatment for serious medical conditions. Before his arrest in 2008 on charges of fraud, Magnitsky had exposed large-scale official corruption.

William Browder, a co-founder and the CEO of the global investment firm Hermitage Capital Management, launched an intense campaign for justice in the death of his friend and lawyer. The resulting Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act of 2012 requires the U.S. government to freeze assets of, and deny visas to, individuals with culpability in Magnitsky’s demise. Those who are guilty of “gross violations” against human rights practitioners and other whistle-blowers are also subject to such sanctions.

The act outraged Russia, which retaliated with prohibitions on adoptions of Russian children by Americans and its own visa bans on U.S. figures allegedly guilty of human rights abuses, including two Guantánamo Bay commanders. Critics in both countries say the act amounts to a new form of blacklisting, paving the way for personal interests to preside over due process in the name of human rights. Supporters—including some of the Russian public, according to a 2012 survey—see it as a means to hold Russia’s powerful to account.

More than two dozen people are now on the “Magnitsky list,” including two named in connection with the 2004 assassination of Forbes journalist Paul Klebnikov. Currently, the Global Human Rights Accountability Act is under consideration by the U.S. Congress. If passed, the same measures of the Magnitsky Act could be applied to any country. Pressure is mounting for the adoption of similar legislation in Europe.

CPJ interviewed Browder, who believes this approach can be used to help raise the cost of impunity for those who attack journalists.

Elisabeth Witchel: What happened when you began to ask questions and look for justice for Sergei Magnitsky’s death in Russia?

William Browder: The Russian government circled the wagons to protect all of the people involved in the torture and death of Sergei and the crimes he had uncovered. They exonerated all of the individuals involved and promoted a number of the most complicit and even gave some of them special state honors.

EW: When did you conclude that you would have to go outside of Russia for any justice?

WB: It was sort of obvious, one or two months into it. A crucial point came about six weeks after his murder. The Moscow Public Oversight Commission concluded that Sergei had been falsely arrested and tortured in custody. They produced a detailed report and sent this to the justice minister and interior minister of Russia. As the weeks passed, there was no response. There was enough evidence to prosecute, but no intention to do anything.

EW: Where did you look to first?

WB: Human rights organizations advised me to go to the [United States] State Department and the European Union. Everyone was sympathetic, but no one was willing to take any action—at best, they were ready to make statements.

EW: The Magnitsky Act sanctions individuals responsible for Magnitsky’s death. How did you decide on this approach? Was there any precedent?

WB: We looked at what process somewhat resembled justice the West actually had the capacity to do—that is, visa sanctions and asset freezes. This was pretty unprecedented. The U.S. and Europe have sanctioned unfriendly regimes like Iran and Belarus, but they never issued sanctions against countries where there were normal relations, like Russia.

EW: What was the response to this idea?

WB: When I proposed it to the [U.S.] State Department in April 2010, they practically laughed me out of their office. They were so busy on the Russian “reset” that they wanted nothing to do with some guy calling for sanctions in the murder of his lawyer.

EW: What changed?

WB: I had an opportunity to raise this through the [U.S.] legislative branch. I went to Sen. Ben Cardin of Maryland, who was invested in human rights through his work with the Helsinki Commission. He analyzed the evidence and then posted a list of 60 Russian officials on the U.S. Helsinki website that he believed should be subject to visa sanctions. This set off a chain reaction, which eventually led to the Magnitsky Act.

EW: Who does the act apply to?

WB: At first, it sanctioned anyone involved in Sergei Magnitsky’s false arrest, torture, and death. This lit up the Moscow sky. After it was published, many other victims came forward. After many of these approaches, Cardin added 65 words to the bill to include all other human rights abusers in Russia to the legislation.

EW: What has been the impact so far?

WB: Now there are 30 people on the list, and I suspect many more will be added in the future. There is federal law in place which will penalize Russian human rights violators. There is also a global Magnitsky Act working its way through Congress which would do this in other countries. I believe this will become the new technology for dealing with human rights abuses. We are living in a different world than, say, 30 years ago, when the Khmer Rouge just stayed in Cambodia. Now human rights abusers travel; bad guys enjoy keeping their money in safer countries. Taking away their ability to do this is one way to punish them. There is no reason you should be guilty of human rights crimes in your country and be able to live in a nice house next to Hyde Park [in central London].

Once this tool starts getting widely implemented, it can be used in a way that allows a state to maintain diplomatic relations with a country but punish individual human rights violators at the same time. We hope this becomes a pedestrian exercise—if governments routinely start to sanction individuals responsible for human rights abuses, the bad guys will start asking the question of whether it is worth it.

EW: Critics of the Magnitsky Act say it is a dangerous path—one that opens the door for abuse and can be used for personal gain. Is this the case?

WB: Not at all. The sanctions are not determined by people like me, but rather by documentary evidence which is reviewed by the U.S. State Department and Treasury. The U.S. government won’t sanction anyone unless they believe the evidence will stand up in a court of law. In our experience, it is an extremely high bar to get someone on the Magnitsky list, specifically because the process is so rigorous and fair.

EW: How can human rights advocates use this against impunity in the killings of journalists? How can they, for example, add a name?

WB: The [U.S.] government adds the names, but civil society can help by collecting evidence and documentation against those who commit these violations and make enough noise to get the government to notice. These sanctions may not be real justice for crimes like torture and murder, but they are far better than absolute impunity, which is what is happening in most places today.